S.h.e.l.t.e.r 0.09 Melissa's Update Download

Living in housing that is below standard or nonexistent

Homelessness is lacking stable and appropriate housing. People can be categorized as homeless if they are: living on the streets (primary homelessness); moving between temporary shelters, including houses of friends, family and emergency accommodation (secondary homelessness); living in private boarding houses without a private bathroom or security of tenure (tertiary homelessness).[1] The legal definition of homeless varies from country to country, or among different jurisdictions in the same country or region.[2] United States government homeless enumeration studies[3] [4] also include people who sleep in a public or private place not designed for use as a regular sleeping accommodation for human beings.[5] [6] People who are homeless are most often unable to acquire and maintain regular, safe, secure and adequate housing due to income that is inconsistent or lacking altogether. Homelessness and poverty are interrelated.[1] There is no methodological consensus on counting homeless people and identifying their needs; therefore in most cities only estimated homeless populations are known.[7]

In 2005, an estimated 100 million people worldwide were homeless and as many as one billion people (one in 6.5 at the time) live as squatters, refugees or in temporary shelter, all lacking adequate housing.[8] [9] [10] Historically in the Western countries, the majority of homeless have been men (50–80%), with single males particularly over represented.[11] [12] [13]

Homeless child and adult living on the streets

When compared to the general population, people who are homeless experience higher rates of adverse physical and mental health outcomes. Chronic disease severity, respiratory conditions, rates of mental health illnesses and substance use are all often greater in homeless populations than the general population.[14] [15] Homelessness is also associated with a high risk of suicide attempts.[16]

There are a number of organizations that provide help for homeless people.[17] Most countries provide a variety of services to assist homeless people. These services often provide food, shelter (beds), and clothing and may be organized and run by community organizations (often with the help of volunteers) or by government departments or agencies. These programs may be supported by the government, charities, churches, and individual donors. Many cities also have street newspapers, which are publications designed to provide employment opportunities to homeless people. While some homeless people have jobs, some must seek other methods to make a living. Begging or panhandling is one option, but is becoming increasingly illegal in many cities. People who are homeless may have additional conditions, such as physical or mental health issues or substance addiction; these issues make resolving homelessness a challenging policy issue.

Definition and classification [edit]

United Nations definition [edit]

In 2004, the United Nations sector of Economic and Social Affairs defined a homeless household as those households without a shelter that would fall within the scope of living quarters due to a lack of a steady income. They carry their few possessions with them, sleeping in the streets, in doorways or on piers, or in another space, on a more or less random basis.[18]

In 2009, at the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Conference of European Statisticians (CES), held in Geneva, Switzerland, the Group of Experts on Population and Housing Censuses defined homelessness as:

In its Recommendations for the Censuses of Population and Housing, the CES identifies homeless people under two broad groups:

(a) Primary homelessness (or rooflessness). This category includes persons living in the streets without a shelter that would fall within the scope of living quarters;

(b) Secondary homelessness. This category may include persons with no place of usual residence who move frequently between various types of accommodations (including dwellings, shelters, and institutions for the homeless or other living quarters). This category includes persons living in private dwellings but reporting 'no usual address on their census form.

The CES acknowledges that the above approach does not provide a full definition of the 'homeless'.[19]

Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted 10 December 1948 by the UN General Assembly, contains this text regarding housing and quality of living:

Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing, and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.[20]

The ETHOS Typology of Homelessness and Housing Exclusion was developed as a means of improving understanding and measurement of homelessness in Europe, and to provide a common "language" for transnational exchanges on homelessness. The ETHOS approach confirms that homelessness is a process (rather than a static phenomenon) that affects many vulnerable households at different points in their lives.[21]

The typology was launched in 2005 and is used for different purposes: as a framework for debate,[22] for data collection purposes, for policy purposes, monitoring purposes, and in the media. This typology is an open exercise that makes abstraction of existing legal definitions in the EU member states. It exists in 25 language versions, the translations being provided mainly by volunteer translators.

Other terms [edit]

Recent homeless enumeration survey documentation utilizes the term unsheltered homeless. The common colloquial term street people does not fully encompass all unsheltered people, in that many such persons do not spend their time in urban street environments. Many shun such locales, because homeless people in urban environments may face the risk of being robbed or assaulted. Some people convert unoccupied or abandoned buildings ("squatting"), or inhabit mountainous areas or, more often, lowland meadows, creek banks, and beaches.[23] Many jurisdictions have developed programs to provide short-term emergency shelter during particularly cold spells, often in churches or other institutional properties. These are referred to as warming centers, and are credited by their advocates as lifesaving.[24]

History [edit]

Early history through the 1800s [edit]

German illustration of a homeless mother and her children in the street, before 1883

Homeless memorial in Toronto, Canada

United Kingdom [edit]

Following the Peasants' Revolt, English constables were authorized under 1383 English Poor Laws statute to collar vagabonds and force them to show support; if they could not, the penalty was gaol.[25] Vagabonds could be sentenced to the stocks for three days and nights; in 1530, whipping was added. The presumption was that vagabonds were unlicensed beggars.[25] In 1547, a bill was passed that subjected vagrants to some of the more extreme provisions of the criminal law, namely two years servitude and branding with a "V" as the penalty for the first offense and death for the second. Large numbers of vagabonds were among the convicts transported to the American colonies in the 18th century.[26] During the 16th century in England, the state first tried to give housing to vagrants instead of punishing them, by introducing bridewells to take vagrants and train them for a profession. In the 17th and 18th centuries, these were replaced by workhouses but these were intended to discourage too much reliance on state help.

United States [edit]

In the Antebellum South, the availability of slave labor made it difficult for poor white people to find work. To prevent poor white people from cooperating with enslaved black people, slaveowners policed poor whites with vagrancy laws.[27]

After American Civil War, a large number of homeless men formed part of a counterculture known as "hobohemia" all over the United States. In smaller towns, hobos temporarily lived near train tracks and hopped onto trains to various destinations.[28] [29]

The growing movement toward social concern sparked the development of rescue missions, such as the U.S. first rescue mission, the New York City Rescue Mission, founded in 1872 by Jerry and Maria McAuley.[30] [31]

Modern [edit]

1900s [edit]

The Great Depression of the 1930s caused a devastating epidemic of poverty, hunger, and homelessness in the United States. When Franklin D. Roosevelt took over the presidency from Herbert Hoover in 1933, he passed the New Deal, which greatly expanded social welfare, including providing funds to build public housing. This marked the end of the Great Depression.[32]

How the Other Half Lives and Jack London's The People of the Abyss (1903) discussed homelessness and raised public awareness, which caused some changes in building codes and some social conditions. In England, dormitory housing called "spikes" was provided by local boroughs. By the 1930s in England, there were 30,000 people living in these facilities. In 1933, George Orwell wrote about poverty in London and Paris, in his book Down and Out in Paris and London. In general, in most countries, many towns and cities had an area that contained the poor, transients, and afflicted, such as a "skid row". In New York City, for example, there was an area known as "the Bowery", traditionally, where people with an alcohol use disorder were to be found sleeping on the streets, bottle in hand.

In the 1960s in the UK, nature and growing problem of homelessness changed in England as public concern grew. The number of people living "rough" in the streets had increased dramatically. However, beginning with the Conservative administration's Rough Sleeper Initiative, the number of people sleeping rough in London fell dramatically. This initiative was supported further by the incoming Labour administration from 2009 onwards with the publication of the 'Coming in from the Cold' strategy published by the Rough Sleepers Unit, which proposed and delivered a massive increase in the number of hostel bed spaces in the capital and an increase in funding for street outreach teams, who work with rough sleepers to enable them to access services.[33]

2000s [edit]

In 2002, research showed that children and families were the largest growing segment of the homeless population in the United States,[34] [35] and this has presented new challenges to agencies.

In the US, the government asked many major cities to come up with a ten-year plan to end homelessness.[ when? ] One of the results of this was a "Housing First" solution. The Housing First program offers homeless people access to housing without having to undergo tests for sobriety and drug usage. The Housing First program seems to benefit homeless people in every aspect except for substance abuse, for which the program offers little accountability.[36] An emerging consensus is that the Housing First program still gives clients a higher chance at retaining their housing once they get it.[37] A few critical voices argue that it misuses resources and does more harm than good; they suggest that it encourages rent-seeking and that there is not yet enough evidence-based research on the effects of this program on the homeless population.[38] Some formerly homeless people, who were finally able to obtain housing and other assets which helped to return to a normal lifestyle, have donated money and volunteer services to the organizations that provided aid to them during their homelessness.[39] Alternatively, some social service entities that help homeless people now employ formerly homeless individuals to assist in the care process.

Homeless children in the United States.[40] The number of homeless children reached record highs in 2011,[41] 2012,[42] and 2013[43] at about three times their number in 1983.[42]

Homelessness has migrated toward rural and suburban areas. The number of homeless people has not changed dramatically but the number of homeless families has increased according to a report of HUD.[44] The United States Congress appropriated $25 million in the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Grants for 2008 to show the effectiveness of Rapid Re-housing programs in reducing family homelessness.[45] [46] [47] In February 2009, President Obama signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, part of which addressed homelessness prevention, allocating $1.5 billion for a Homeless Prevention Fund. The Emergency Shelter Grant (ESG) program's name was changed to Emergency Solution Grant (ESG) program, and funds were re-allocated to assist with homeless prevention and rapid re-housing for families and individuals.[48]

[edit]

Causes [edit]

Major reasons and information about homelessness as documented by many reports and studies include:[49] [50] [51] [52] [53]

- Domestic violence. Compared to housed women, homeless women were more likely to report childhood histories of abuse, as well as more current physical abuse by male partners.[54]

- Forced eviction. In many countries, people lose their homes by government orders to make way for newer upscale high-rise buildings, roadways, and other governmental needs.[55] The compensation may be minimal, in which case the former occupants cannot find appropriate new housing and become homeless.

- Foreclosures on landlords often lead to the eviction of their tenants. "The Sarasota, Florida, Herald Tribune noted that, by some estimates, more than 311,000 tenants nationwide have been evicted from homes this year after lenders took over the properties."[49] [56]

- Gender. The experiences of homeless women and women in poverty are often overlooked, however, they experience specific gender-based victimization. As individuals with little to no physical or material capital, homeless women are particularly targeted by male law enforcement and men living on the street. It has been found that "street-based homelessness dominates mainstream understanding of homelessness and it is indeed an environment in which males have far greater power (O'Grady and Gaietz, 2004)."[57] Women on the street are often motivated to gain capital through affiliation and relationships with men, rather than facing homelessness alone. Within these relationships, women are still likely to be physically and sexually abused.[57]

- Gentrification, the process where a neighborhood becomes popular with wealthier people, and the poor residents are priced out

- Lack of accessible healthcare

- Lack of affordable housing. In Oregon specifically, inadequate housing is also a driver of foster care placements increasing from 13% to 17% over a two-year period of time.[58]

- Transitions from foster care and other public systems; specifically youth who have been involved in or are a part of the foster care system are more likely to become homeless. Most leaving the system have no support and no income, making it nearly impossible to break the cycle and forcing them to live on the streets. There is also a lack of shelter beds for youth; various shelters have strict and stringent admissions policies.[59]

- Disability, especially where disability services are non-existent, inconvenient, or poorly performing[60]

- Afflicted with a mental disorder, where mental health services are unavailable or difficult to access.[61] A United States federal survey done in 2005 indicated that at least one-third of homeless men and women have serious psychiatric disorders or problems. Autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia are the top two common mental disabilities among the U.S. homeless. Personality disorders are also very prevalent, especially Cluster A.[62] [63]

- Migration, either domestic or foreign to the country, where the number of migrants outstrips the supply of affordable housing

- Mortgage foreclosures where mortgage holders see the best solution to a loan default is to take and sell the house to pay off the debt. The popular press made an issue of this in 2008.[64]

- Natural disasters, including but not limited to earthquakes and hurricanes[65]

- Poverty, caused by many factors including unemployment and underemployment

- Prison release and re-entry into society

- Relationship breakdown, particularly in relation to young people and their parents, such as disownment[66]

- Social exclusion related to sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or sex characteristics (e.g., LGBT+)[67]

- Substance use disorder or addiction, such as alcohol use disorder

- Traumatic brain injury, a condition which, according to a Canadian survey, is widespread among homeless people and, for around 70% of respondents, can be attributed to a time "before the onset of homelessness"[68]

- War or armed conflict, which can create refugees fleeing the violence

- Choice. Although uncommon, some choose to be homeless as a personal lifestyle choice.[ citation needed ]

A substantial percentage of the US homeless population are individuals who are chronically unemployed or have difficulty managing their lives effectively due to prolonged and severe substance or alcohol use.[69] Substance abuse can cause homelessness from behavioral patterns associated with addiction that alienate an addicted individual's family and friends who could otherwise provide support during difficult economic times. Increased wealth disparity and income inequality causes distortions in the housing market that push rent burdens higher, making housing unaffordable.[70] Paul Koegel of RAND Corporation, a seminal researcher in first-generation homelessness studies and beyond, divided the causes of homelessness into structural aspects and then individual vulnerabilities.[53]

Challenges [edit]

The basic problem of homelessness is the need for personal shelter, warmth, and safety. Other difficulties include:

- Hygiene and sanitary facilities

- Hostility from the public and laws against urban vagrancy

- Cleaning and drying of clothes

- Obtaining, preparing, and storing food

- Keeping contact with friends, family, and government service providers without a permanent location or mailing address

- Medical problems, including issues caused by an individual's homeless state (e.g., hypothermia or frostbite from sleeping outside in cold weather), or issues which are exacerbated by homelessness due to lack of access to treatment (e.g., mental health and the individual not having a place to store prescription drugs for conditions such as schizophrenia)

- Personal security, quiet, and privacy, especially for sleeping, bathing, and other hygiene activities

- Safekeeping of bedding, clothing, and possessions, which may have to be carried at all times

Homeless people face many problems beyond the lack of a safe and suitable home. They are often faced with reduced access to private and public services and vital necessities:[71]

- General rejection or discrimination from other people

- Increased risk of suffering violence and abuse

- Limited access to education

- Loss of usual relationships with the mainstream

- Not being seen as suitable for employment

- Reduced access to banking services

- Reduced access to communications technology

- Reduced access to healthcare and dental services

- Targeting by municipalities to exclude from public space[72]

- Implication of hostile architecture[73]

- Difficulty forming trust in relation to services, systems, and other people; exacerbating pre-existing difficulty accessing aid and escaping homelessness, particularly present in the chronically homeless[74]

There is sometimes corruption and theft by the employees of a shelter, as evidenced by a 2011 investigative report by FOX 25 TV in Boston wherein a number of Boston public shelter employees were found stealing large amounts of food over a period of time from the shelter's kitchen for their private use and catering.[75] [76] Homeless people are often obliged to adopt various strategies of self-presentation in order to maintain a sense of dignity, which constrains their interaction with passers-by and leads to suspicion and stigmatization by the mainstream public.[77]

Homelessness is also a risk factor for depression caused by prejudice. When someone is prejudiced against people who are homeless and then becomes homeless themselves, their anti-homelessness prejudice turns inward, causing depression. "Mental disorders, physical disability, homelessness, and having a sexually transmitted infection are all stigmatized statuses someone can gain despite having negative stereotypes about those groups."[78] Difficulties can compound exponentially. A study found that in the city of Hong Kong over half of the homeless people in the city (56%) had some degree of mental illness. Only 13% of the 56% were receiving treatment for their condition leaving a huge portion of homeless untreated for their mental illness.[79]

The issue of anti-homeless architecture came to light in 2014 after a photo displayed hostile features (spikes on the floor) in London and took social media by storm. The photo of an anti-homeless structure was a classic example of hostile architecture in an attempt to discourage people from attempting to access or use public space in irregular ways. However, although this has only recent came to light, hostile architecture has been around for a long time in many places.[80] : 68 An example of this is a low overpass that was put in place between New York City and Long Island. Robert Moses was the artist that designed it this way in an attempt to ban public buses from being able to pass through it.[81]

Victimization by violent crimes [edit]

Homeless people are often the victims of violent crime. A 2007 study found that the rate of violent crimes against homeless people in the United States is increasing.[82] A study of women veterans found that homelessness is associated with domestic violence, both directly as the result of leaving an abusive partner and indirectly due to trauma, mental health conditions, and substance abuse.[83]

Rent control [edit]

Rent regulation has a small effect on shelter and street populations.[84] This is largely due to rent control reducing the quality and quantity of housing. For example, a 2019 study found that San Francisco's rent control laws reduced tenant displacement from rent controlled units in the short-term, but resulted in landlords removing 30% of the rent controlled units from the rental market, (by conversion to condos or TICs) which led to a 15% citywide decrease in total rental units, and a 7% increase in citywide rents.[85]

Stigma [edit]

Conditions such as alcohol use disorder and mental illness are often associated with homelessness.[86] Many people fear homeless people due to the stigma surrounding the homeless community. Surveys have revealed that before spending time with the homeless, most people fear them, but after spending time with homeless people, that fear is lessened or is no longer there.[87] Another effect of this stigma is isolation.[88]

Assistance and resources [edit]

Most countries provide a variety of services to assist homeless people. Provisions of food, shelter, and clothing and may be organized and run by community organizations, often with the help of volunteers, or by government departments. Assistance programs may be supported by government, charities, churches, and individual donors. In 1998, a study by Koegel and Schoeni of a homeless population in Los Angeles, California, found that a significant minority of homeless did not participate in government assistance programs, with high transaction costs being a likely contributing factor.[89]

The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development and Veterans Administration have a special Section 8 housing voucher program called VASH (Veterans Administration Supported Housing), or HUD-VASH, which gives out a certain number of Section 8 subsidized housing vouchers to eligible homeless and otherwise vulnerable US armed forces veterans.[90] The HUD-VASH program has shown success in housing many homeless veterans.[91] The support available to homeless veterans varies internationally, however. For example, in England, where there is a national right to housing, veterans are only prioritized by local authority homelessness teams if they are found to be vulnerable due to having served in the Armed Forces.[92]

Non-governmental organizations also house or redirect homeless veterans to care facilities. Social Security Income/Social Security Disability Income, Access, Outreach, Recovery Program (SOAR) is a national project funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. It is designed to increase access to SSI/SSDI for eligible adults who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless and have a mental illness or a co-occurring substance use disorder. Using a three-pronged approach of Strategic Planning, Training, and Technical Assistance (TA), the SOAR TA Center coordinates this effort at the state and community level.[93]

[edit]

While some homeless people are known to have a community with one another,[94] providing each other various types of support,[95] people who are not homeless also may provide them friendship, food, relational care, and other forms of assistance. Such social supports may occur through a formal process, such as under the auspices of a non-governmental organization, religious organization, or homeless ministry, or may be done on an individual basis. In Los Angeles, a collaboration between the Ostrow School of Dentistry of the University of Southern California and the Union Rescue Mission shelter offer homeless people in the Skid Row area free dental services.[96]

Income sources [edit]

Homeless people can also provide waste management services to earn money. Some homeless people find returnable bottles and cans and bring them to recycling centers to earn money. For example, they can sort out organic trash from other trash or separate out trash made of the same material (for example, different types of plastics, and different types of metal). Especially in Brazil, many people are already engaged in such activities.[97] In addition, rather than sorting waste at landfills, ... they can also collect litter found on/beside the road to earn an income.[98] Invented in 2005, in Seattle, Bumvertising, an informal system of hiring homeless people to advertise, has provided food, money, and bottles of water to sign-holding homeless in the Northwest. Homeless advocates have accused its founder, Ben Rogovy, and the process, of exploiting the poor and take particular offense to the use of the word "bum" which is generally considered pejorative.[99] [100] In October 2009, The Boston Globe carried a story on so-called cyberbegging, or Internet begging, which was reported to be a new trend worldwide.[101] Income assistance appears to be effective in improving housing outcomes.[102] Cost increases associated with income assistance appear to be offset by the benefits it provides.[102]

Employment [edit]

The United States Department of Labor has sought to address one of the main causes of homelessness, a lack of meaningful and sustainable employment, through targeted training programs and increased access to employment opportunities that can help homeless people develop sustainable lifestyles.[103] This has included the development of the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness, which addresses homelessness on the federal level in addition to connecting homeless individuals to resources at the state level.[104] All individuals who are in need of assistance are able, in theory, to access employment and training services under the Workforce Investment Act (WIA), although this is contingent upon funding and program support by the government, with veterans also being able to use the Veterans Workforce Investment Program.[103]

Under the Department of Labor, the Veterans' Employment and Training Service (VETS) offers a variety of programs targeted at ending homelessness among veterans.[103] The Homeless Veterans' Reintegration Program (HVRP) is the only national program that is exclusively focused on assisting veterans as they reenter the workforce.[103] The VETS program also has an Incarcerated Veterans' Transition Program, as well as services that are unique to female Veterans.[103] Mainstream programs initiated by the Department of Labor have included the Workforce Investment Act, One-Stop Career Centers, and a Community Voice Mail system that helps to connect homeless individuals around the United States with local resources.[105] Targeted labor programs have included the Homeless Veterans' Reintegration Project, the Disability Program Navigator Initiative, efforts to end chronic homelessness through providing employment and housing projects, Job Corps, and the Veterans Workforce Investment Program (VWIP).[105]

Street newspapers [edit]

Street newspapers are newspapers or magazines sold by homeless or poor individuals and produced mainly to support these populations. Most such newspapers primarily provide coverage about homelessness and poverty-related issues and seek to strengthen social networks within homeless communities, making them a tool for allowing homeless individuals to work.[106]

Housing [edit]

Permanent supportive housing (PSH) interventions appear to have improvements in housing stability for people living with homelessness even in long-term. [107] [102]

Organizing in homeless shelters [edit]

Homeless shelters can become grounds for community organization and the recruitment of homeless individuals into social movements for their own cause. Cooperation between the shelter and an elected representative from the homeless community at each shelter can serve as the backbone of this type of initiative. The representative presents and forwards problems raises concerns and provides new ideas to the director and staff of the shelters. Examples of possible problems are ways to deal with substance use disorders by certain shelter users, and resolution of interpersonal conflicts. SAND, the Danish National Organization for Homeless People, is one example of an organization that uses this empowerment approach.[108] Issues reported at the homeless shelters are then addressed by SAND at the regional or national level. To open further dialogue, SAND organizes regional discussion forums where staff and leaders from the shelters, homeless representatives, and local authorities meet to discuss issues and good practices at the shelters.[109]

Homeless Housing Innovations [edit]

Los Angeles conducted a competition promoted by Mayor Eric Garcetti soliciting ideas from developers to use bond money more efficiently in building housing for the city's homeless population. The top five winners were announced on 1 February 2019 and the concepts included using assembly-ready molded polymer panels that can be put together with basic tools, prefabricated 5-story stack-able houses, erecting privately financed modular buildings on properties that do not require City Council approval, using bond money to convert residential garages into small apartments which are then dedicated to homeless rentals, and the redeveloping of Bungalow-court units, the small low-income iconic buildings that housed 7% of the city's population in the 1920s.[110]

In the neighborhood of Westlake, Los Angeles, the city is funding the first transitionally homeless housing building using "Cargotecture", or "architecture built from repurposed shipping containers." The Hope on Alvarado micro-apartment building will consist of 4-stories of 84 containers stacked together like Lego bricks on top of a traditionally constructed ground floor. Completion is anticipated by the end of 2019.[111]

Political action: voting [edit]

Voting for elected officials is important for the homeless population to have a voice in the democratic process.[109]

Services [edit]

There are many community organizations and social movements around the world which are taking action to reduce homelessness. They have sought to counteract the causes and reduce the consequences by starting initiatives that help homeless people transition to self-sufficiency. Social movements and initiatives tend to follow a grassroots, community-based model of organization – generally characterized by a loose, informal and decentralized structure, with an emphasis on radical protest politics. By contrast, an interest group aims to influence government policies by relying on more of a formal organizational structure.[109] These groups share a common element: they are both made up of and run by a mix of allies of the homeless population and former or current members of the homeless population. Both grassroots groups and interest groups aim to break stereotyped images of homeless people as being weak and hapless, or defiant criminals and drug addicts, and to ensure that the voice of homeless people and their representatives is clearly heard by policymakers.

Accommodation-based approaches are mostly effective for increasing housing stability and health outcomes, with many interventions having evolved to incorporate support and services beyond delivery of housing, including health, employment, crime and wellbeing. An accommodation-based approach which provides the highest levels of support and does not place rules on the person receiving the intervention is best at improving housing stability and health outcomes. For an intervention to work best, it must have a balance of staff, resources, time and engagement of the person experiecing homelessness. On the other hand, interventions which are described as Basic/Unconditional (i.e., those that only satisfy very basic human needs such as a bed and food) harm people: meaning they had worse health and housing stability outcomes even when compared to receiving nothing at all.[112]

Housing [edit]

Homeless shelter in Poznan, Poland

Urban homeless shelters [edit]

Many homeless people keep all their possessions with them because they have no access to storage. There have been "bag" people, shopping cart people, and soda can collectors (known as binners or dumpster divers) who sort through garbage to find items to sell, trade, or eat. Such people have typically carried all their possessions with them all the time. If they had no access to or ability to get to a shelter and possible bathing, or access to toilets and laundry facilities, their hygiene was lacking. This has created social tensions in public places.[ citation needed ]

These conditions have created an upsurge in tuberculosis and other diseases in urban areas.[113] [114] [115]

Refuges and alternative accommodation [edit]

There are various places where a homeless person might seek refuge:

- 24-hour Internet cafes are now used by over 5,000 Japanese "Net cafe refugees". An estimated 75% of Japan's 3,200 all-night internet cafes cater to regular overnight guests, who in some cases have become their main source of income.[116]

- 24-hour McDonald's restaurants are used by "McRefugees" in Japan, China and Hong Kong. There are about 250 McRefugees in Hong Kong.[117]

- Couch surfing: temporary sleeping arrangements in dwellings of friends or family members ("couch surfing"). This can also include housing in exchange for labor or sex. Couch surfers may be harder to recognize than street homeless people and are often omitted from housing counts.[118]

- Homeless shelters: including emergency cold-weather shelters opened by churches or community agencies, which may consist of cots in a heated warehouse, or temporary Christmas Shelters. More elaborate homeless shelters such as Pinellas Hope in Florida provide residents with a recreation tent, a dining tent, laundry facilities, outdoor tents, casitas, and shuttle services that help inhabitants get to their jobs each day.[119]

- Inexpensive boarding houses: have also been called flophouses. They offer cheap, low-quality temporary lodging.

- Inexpensive motels offer cheap, low-quality temporary lodging. However, some who can afford housing live in a motel by choice. For example, David and Jean Davidson spent 22 years at various UK Travelodges.[120]

- Public places: Parks, bus or train stations, public libraries, airports, public transportation vehicles (by continual riding where unlimited passes are available), hospital lobbies or waiting areas, college campuses, and 24-hour businesses such as coffee shops. Many public places use security guards or police to prevent people from loitering or sleeping at these locations for a variety of reasons, including image, safety, and comfort of patrons.[121] [122]

- Shantytowns: ad hoc dwelling sites of improvised shelters and shacks, usually near rail yards, interstates and high transportation veins. Some shantytowns have interstitial tenting areas, but the predominant feature consists of hard structures. Each pad or site tends to accumulate roofing, sheathing, plywood, and nailed two by fours.

- Single room occupancy (more commonly abbreviated to SRO):a form of housing that is typically aimed at residents with low or minimal incomes who rent small, furnished single rooms with a bed, chair, and sometimes a small desk.[123] SRO units are rented out as permanent residence or primary residence[124] to individuals, within a multi-tenant building where tenants share a kitchen, toilets or bathrooms. In the 2010s, some SRO units may have a small refrigerator, microwave and sink.[123] (also called a "residential hotel").

- Squatting in an unoccupied structure where a homeless person may live without payment and without the owner's knowledge or permission. Often these buildings are long abandoned and not safe to occupy.

- Tent cities: ad hoc campsites of tents and improvised shelters consisting of tarpaulins and blankets, often near industrial and institutionally zoned real estate such as rail yards, highways and high transportation veins. A few more elaborate tent cities, such as Dignity Village, are hybrids of tent cities and shantytowns. Tent cities frequently consist only of tents and fabric improvised structures, with no semi-permanent structures at all.

- Outdoors: on the ground or in a sleeping bag, tent, or improvised shelter, such as a large cardboard box, under a bridge, in an urban doorway, in a park or a vacant lot.

- Tunnels such as abandoned subway, maintenance, or train tunnels are popular among the long-term or permanent homeless.[125] [126] The inhabitants of such refuges are called in some places, like New York City, "Mole People". Natural caves beneath urban centers allow for places where people can congregate. Leaking water pipes, electric wires, and steam pipes allow for some of the essentials of living.

- Vehicles: cars or trucks used as temporary or sometimes long-term living quarters, for example by those recently evicted from a home. Some people live in recreational vehicles (RVs), school buses, vans, sport utility vehicles, covered pickup trucks, station wagons, sedans, or hatchbacks. The vehicular homeless, according to homeless advocates and researchers, comprise the fastest-growing segment of the homeless population.[127] Many cities have safe parking programs in which lawful sites are permitted at churches or in other out-of-the-way locations. For example, because it is illegal to park on the street in Santa Barbara, the New Beginnings Counseling Center worked with the city to make designated parking lots available to homeless people.[119]

Other housing options [edit]

Transitional housing

Transitional housing provides temporary housing for certain segments of the homeless population, including the working homeless, and is meant to transition residents into permanent, affordable housing. This is usually a room or apartment in a residence with support services. The transitional time can be relatively short, for example, one or two years, and in that time the person must file for and obtain permanent housing along with gainful employment or income, even if Social Security or assistance. Sometimes transitional housing programs charge a room and board fee, maybe 30% of an individual's income, which is sometimes partially or fully refunded after the person procures a permanent residence. In the U.S., federal funding for transitional housing programs was originally allocated in the McKinney–Vento Homeless Assistance Act of 1986.[128] [129] [130]

Foyers

Foyers are a specific type of transitional housing designed for homeless or at-risk teens. Foyers are generally institutions that provide affordable accommodation as well as support and training services for residents. They were pioneered in the 1990s in the United Kingdom, but have been adopted in areas in Australia and the United States as well.

Supportive housing

Supportive housing is a combination of housing and services intended as a cost-effective way to help people live more stable, productive lives. Supportive housing works well for those who face the most complex challenges – individuals and families confronted with homelessness who also have very low incomes or serious, persistent issues such as substance use disorder, addictions, alcohol use disorder, mental illness, HIV/AIDS, or other serious challenges. A 2021 systematic review of 28 interventions, mostly in North America, showed that interventions with highest levels of support led to improved outcomes for both housing stability, and health outcomes.[131] [132]

Government initiatives

In South Australia, the state government of Premier Mike Rann (2002–2011) committed substantial funding to a series of initiatives designed to combat homelessness. Advised by Social Inclusion Commissioner David Cappo and the founder of New York's Common Ground program, Rosanne Haggerty, the Rann government established Common Ground Adelaide,[133] building high-quality inner city apartments (combined with intensive support) for "rough sleeping" homeless people. The government also funded the Street to Home program and a hospital liaison service designed to assist homeless people admitted to the emergency departments of Adelaide's major public hospitals. Rather than being released back into homelessness, patients identified as rough sleepers were found accommodation backed by professional support. Common Ground and Street to Home now operate across Australia in other States.[134]

Savings from housing homeless in the US [edit]

In 2013, a Central Florida Commission on Homelessness study indicated that the region spends $31,000 a year per homeless person to cover "salaries of law enforcement officers to arrest and transport homeless individuals – largely for nonviolent offenses such as trespassing, public intoxication or sleeping in parks – as well as the cost of jail stays, emergency room visits and hospitalization for medical and psychiatric issues. This did not include "money spent by nonprofit agencies to feed, clothe and sometimes shelter these individuals". In contrast, the report estimated the cost of permanent supportive housing at "$10,051 per person per year" and concluded that "[h]ousing even half of the region's chronically homeless population would save taxpayers $149 million over the next decade – even allowing for 10 percent to end up back on the streets again." This particular study followed 107 long-term-homeless residents living in Orange, Osceola or Seminole Counties.[135] There are similar studies showing large financial savings in Charlotte and Southeastern Colorado from focusing on simply housing the homeless."[136]

In general, housing interventions had mixed economic results on cost-analysis studies.[102]

Standard Case Management [edit]

Standard case management entails several services where homeless people with multiple health problems are supported by case managers in accessing social, health-care and other services in order to maintain good health and social relationships.[102] This type of intervention has showed the potential to improve housing, however it did not show benefits on cost-analysis.[102]

Health care [edit]

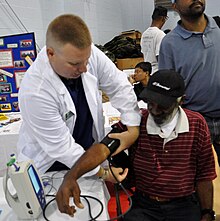

Student nurse at Jacksonville University School of Nursing takes the blood pressure of a homeless veteran during the annual Stand Down for Homelessness activity in Savannah, Georgia.

Health care for homeless people is a major public health challenge.[137] Homeless people are more likely to suffer injuries and medical problems from their lifestyle on the street, which includes poor nutrition,[138] exposure to the severe elements of weather, and a higher exposure to violence. Yet at the same time, they have reduced access to public medical services or clinics,[139] in part because they often lack identification or registration for public healthcare services. There are significant challenges in treating homeless people who have psychiatric disorders because clinical appointments may not be kept, their continuing whereabouts are unknown, their medicines may not be taken as prescribed, medical and psychiatric histories are not accurate, and other reasons. Because many homeless people have mental illnesses, this has presented a crisis in care.[61] [140] [141]

Homeless people may find it difficult to document their date of birth or their address. Because homeless people usually have no place to store possessions, they often lose their belongings, including identification and other documents, or find them destroyed by police or others. Without a photo ID, homeless persons cannot get a job or access many social services, including healthcare. They can be denied access to even the most basic assistance: clothing closets, food pantries, certain public benefits, and in some cases, emergency shelters. Obtaining replacement identification is difficult. Without an address, birth certificates cannot be mailed. Fees may be cost-prohibitive for impoverished persons. And some states will not issue birth certificates unless the person has photo identification, creating a Catch-22.[142] This problem is far less acute in countries that provide free-at-use health care, such as the UK, where hospitals are open-access day and night and make no charges for treatment. In the U.S., free-care clinics for homeless people and other people do exist in major cities, but often attract more demand than they can meet.[143]

The conditions affecting homeless people are somewhat specialized and have opened a new area of medicine tailored to this population. Skin conditions, including scabies, are common because homeless people are exposed to extreme cold in the winter and have little access to bathing facilities. They have problems caring for their feet[144] and have more severe dental problems than the general population.[145] Diabetes, especially untreated, is widespread in the homeless population.[146] Specialized medical textbooks have been written to address this for providers.[147]

There are many organizations providing free care to homeless people in countries which do not offer free state-run medical treatment, but the services are in great demand given the limited number of medical practitioners. For example, it might take months to get a minimal dental appointment in a free-care clinic. Communicable diseases are of great concern, especially tuberculosis, which spreads more easily in crowded homeless shelters in high-density urban settings.[148] There has been ongoing concern and studies about the health and wellness of the older homeless population, typically ages 50 to 64, and older, as to whether they are significantly more sickly than their younger counterparts and if they are under-served.[149] [150]

In 1985, the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program was founded to assist the growing numbers of homeless living on the streets and in shelters in Boston and who were suffering from a lack of effective medical services.[151] [152] In 2004, Boston Health Care for the Homeless in conjunction with the National Health Care for the Homeless Council published a medical manual called The Health Care of Homeless Persons, edited by James J. O'Connell, M.D., specifically for the treatment of the homeless population.[153] In June 2008 in Boston, the Jean Yawkey Place, a four-story, 7,214.2-square-metre (77,653 sq ft) building, was opened by the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program. It is an entire full-service building on the Boston Medical Center campus dedicated to providing healthcare for homeless people. It also contains a long-term care facility, the Barbara McInnis House, which expanded to 104 beds and is the first and largest medical respite program for homeless people in the United States.[154] [155] [156]

A 2011 study led by Dr. RebeccaT. Brown in Boston, conducted by the Institute for Aging Research (an affiliate of Harvard Medical School), Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program found the elderly homeless population had "higher rates of geriatric syndromes, including functional decline, falls, frailty and depression than seniors in the general population and that many of these conditions may be easily treated if detected". The report was published in the Journal of Geriatric Internal Medicine.[157] There are government avenues which provide resources for the development of healthcare for homeless people. In the United States, the Bureau of Primary Health Care has a program that provides grants to fund the delivery of healthcare to homeless people.[158] According to 2011 UDS data community health centers were able to provide service to 1,087,431 homeless individuals.[159] There are also many nonprofit and religious organizations which provide healthcare services to homeless people. These organizations help meet the large need which exists for expanding healthcare for homeless people.

The 2010 passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act could provide new healthcare options for homeless people in the United States, particularly through the optional expansion of Medicaid. A 2013 Yale study indicated that a substantial proportion of the chronically homeless population in America would be able to obtain Medicaid coverage if states expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act.[160]

There have been significant numbers of unsheltered persons dying of hypothermia, adding impetus to the trend of establishing warming centers as well as extending enumeration surveys with vulnerability indexes.[161] [162]

Studies on the effects of intensive mental health interventions have demonstrated some improvements in housing stability and to be economically beneficial on cost-analysis.[102]

Effect on life expectancy [edit]

In 1999, Dr. Susan Barrow of the Columbia University Center for Homelessness Prevention Studies reported in a study that the "age-adjusted death rates of homeless men and women were four times those of the general U.S. population and two to three times those of the general population of New York City".[163] A report commissioned by homeless charity Crisis in 2011 found that on average, homeless people in the UK have a life expectancy of 47 years, 30 years younger than the rest of the population.[164]

Health impacts of extreme weather events [edit]

People experiencing homelessness are at a significant increased risk to the effects of extreme weather events. Such weather events include extreme heat and cold, floods, storm surges, heavy rain and droughts. While there are many contributing factors to these events, climate change is driving an increasing frequency and intensity of these events.[165] The homeless population is considerably more vulnerable to these weather events due to their higher rates of chronic disease and lower socioeconomic status. Despite having a minimal carbon footprint, homeless people unfortunately experience a disproportionate burden of the effects of climate change.[166]

Homeless persons have increased vulnerability to extreme weather events for many reasons. They are disadvantaged in most social determinants of health, including lack of housing and access to adequate food and water, reduced access to health care, and difficulty in maintaining health care.[166] They have significantly higher rates of chronic disease including respiratory disease and infections, gastrointestinal disease, musculoskeletal problems and mental health disease.[167] In fact, self-reported rates of respiratory diseases (including asthma, chronic bronchitis and emphysema) are double that of the general population.[166]

The homeless population often live in higher risk urban areas with increased exposure and little protection from the elements. They also have limited access to clean drinking water and other methods of cooling down.[167] The built environment in urban areas also contributes to the "heat island effect", the phenomenon whereby cities experience higher temperatures due to the predominance of dark, paved surfaces and lack of vegetation.[168] Homeless populations are often excluded from disaster planning efforts, further increasing their vulnerability when these events occur.[169] Without the means to escape extreme temperatures and seek proper shelter and cooling or warming resources, homeless people are often left to suffer the brunt of the extreme weather.

The health effects that result from extreme weather include exacerbation of chronic diseases and acute illnesses. Pre-existing conditions can be greatly exacerbated by extreme heat and cold, including cardiovascular, respiratory, skin and renal disease, often resulting in higher morbidity and mortality during extreme weather. Acute conditions such as sunburn, dehydration, heat stroke and allergic reactions are also common. In addition, a rise in insect bites can lead to vector-borne infections.[167] Mental health conditions can also be impacted by extreme weather events as a result of lack of sleep, increased alcohol consumption, reduced access to resources and reduced ability to adjust to the environmental changes.[167] In fact, pre-existing psychiatric illness has been shown to triple the risk of death from extreme heat.[170] Overall, extreme weather events appear to have a "magnifying effect" in exacerbating the underlying prevalent mental and physical health conditions of homeless populations.[169]

Case study: Hurricane Katrina [edit]

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina, a category 5 hurricane, made landfall on Florida and Louisiana. It particularly affected the city of New Orleans and the surrounding areas. Hurricane Katrina was the deadliest hurricane in the US in seven decades with more than 1,600 confirmed deaths and more than 1,000 people missing. The hurricane disproportionately affected marginalized individuals and individuals with lower socioeconomic status (i.e., 93% of shelter residents were African–American, 32% had household incomes below $10,000/year and 54% were uninsured).[166] The storm nearly doubled the number of homeless people in New Orleans. While in most cities homeless people account for 1% of the population, in New Orleans' the homeless account for 4% of the population. In addition to its devastating effects on infrastructure and the economy, the estimated prevalence of mental illness and the incidence of West Nile Virus more than doubled after Hurricane Katrina in the hurricane-affected regions.[166]

Standard Case Management [edit]

Standard case management entails several services where homeless people with multiple health problems are supported by case managers in accessing social, health-care and other services necessary for maintaining good health and social relationships. This intervention has showed some potential to improve housing[102]

Global statistics [edit]

Demographics [edit]

Homeless man sleeping in London, 2015

In western countries such as the United States, the typical homeless person is male and single,[171] with the Netherlands reporting 80% of homeless people aged 18–65 to be men. Some cities have particularly high percentages of males in homeless populations, with men comprising eighty-five percent of the homeless in Dublin.[172] Non-white people are also overrepresented in homeless populations, with such groups two and one-half times more likely to be homeless in the U.S. The median age of homeless people is approximately 35.[173]

Statistics for developed countries [edit]

In 2005, an estimated 100 million people worldwide were homeless.[174] The following statistics indicate the approximate average number of homeless people at any one time. Each country has a different approach to counting homeless people, and estimates of homelessness made by different organizations vary wildly, so comparisons should be made with caution.

- European Union: 3,000,000 (UN-HABITAT 2004)

- United Kingdom: 10,459 rough sleepers, 98,750 households in temporary accommodation (Department for Communities and Local Government 2005)

- Canada: 150,000[175]

- Australia: On census night in 2006 there were 105,000 people homeless across Australia, an increase from the 99,900 Australians who were counted as homeless in the 2001 census[176]

- United States:[177] The HUD 2018 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress reports that in a single night, roughly 553,000 people were experiencing homelessness in the United States.[178] According to HUD's July 2010 5th Homeless Assessment Report to Congress, in a single night in January 2010, single-point analysis reported to HUD showed 649,917 people experiencing homelessness. This number had increased from January 2009's 643,067. The unsheltered count increased by 2.8 percent while the sheltered count remained the same. Also, HUD reported the number of chronically homeless people (persons with severe disabilities and long homeless histories) decreased one percent between 2009 and 2010, from 110,917 to 109,812. Since 2007 this number had decreased by 11 percent. This was mostly due to the expansion of permanent supportive housing programs.

- The change in numbers has occurred due to the prevalence of homelessness in local communities rather than other changes. According to HUD's July 2010 Homeless Assessment Report to Congress, more than 1.59 million people spent at least one night in an emergency shelter or transitional housing program during the 2010 reporting period, a 2.2 percent increase from 2009. Most users of homeless shelters used only an emergency shelter, while 17 percent used only transitional housing, and less than 5 percent used both during the reporting period. Since 2007, the annual number of those using homeless shelters in cities has decreased from 1.22 million to 1.02 million, a 17 percent decrease. The number of persons using homeless shelters in suburban and rural areas increased 57 percent, from 367,000 to 576,000.[179] In the U.S., the federal government's HUD agency has required federally-funded organizations to use a computer tracking system for homeless people and their statistics, called HMIS (Homeless Management Information System).[180] [181] [182] There has been some opposition to this kind of tracking by privacy advocacy groups, such as EPIC.[183]

- However, HUD considers its reporting techniques to be reasonably accurate for homeless in shelters and programs in its Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress.[184] [185] Actually determining and counting the number of homeless is very difficult in general due to their lifestyle habits.[186] [187] There are so-called "hidden homeless" out of sight of the normal population and perhaps staying on private property.[188] Various countries, states, and cities have come up with differing means and techniques to calculate an approximate count. For example, a one night "homeless census count", called a point-in-time (PIT) count, usually held in early winter for the year, is a technique used by a number of American cities, such as Boston.[189] [190] [191] Los Angeles uses a mixed set of techniques for counting, including the PIT street count.[188] [192]

- In 2003, The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) had begun requiring a PIT count in all "Continuum of Care" communities which required them to report a count of people, housing status, and geographic locations of individuals counted. Some communities provide sub-population information to the PIT, such as information on veterans, youth, and elderly individuals, as done in Boston.[193]

- Japan: 20,000–100,000 (some figures put it at 200,000–400,000).[194] Reports show that homelessness is on the rise in Japan since the mid-1990s.[195] There are more homeless men than homeless women in Japan because it is usually easier for women to get a job and they are less isolated than men. Also Japanese families usually provide more support for women than they do for men.[196]

Developing and undeveloped countries [edit]

The number of homeless people worldwide has grown steadily in recent years.[197] [198] In some developing countries such as Nigeria and South Africa, homelessness is rampant, with millions of children living and working on the streets.[199] [200] Homelessness has become a problem in the countries of China, India, Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines despite their growing prosperity, partly due to migrant workers who have trouble finding permanent homes.[201] [ dead link ]

Determining the true number of homeless people worldwide varies between 100 million and 1 billion people based on the exact definition used.[202] Refugees, asylum-seekers, and internally displaced persons can also be considered homeless in that they, too, experience "marginalization, minority status, socioeconomic disadvantage, poor physical health, collapse of social supports, psychological distress, and difficulty adapting to host cultures" such as the domestic homeless.[203]

In the past twenty years, scholars such as Tipple and Speak have begun to refer to homelessness as the "antithesis or absence of home" rather than rooflessness or the "lack of physical shelter." This complication in the homelessness debate further delineates the idea that home actually consists of an adequate shelter, an experienced and dynamic place that serves as a "base" for nurturing human relationships and the "free development of individuals" and their identity.[204] Thus, the home is perceived to be an extension of one's self and identity. In contrast, the homeless experience, according to Moore, constitutes more as a "lack of belonging" and a loss of identity that leads to individuals or communities feeling "out of place" once they can no longer call a place of their own home.[205]

This new perspective on homelessness sheds light on the plight of refugees, a population of stateless people who are not normally included in the mainstream definition of homelessness. It has also created problems for researchers because the nature of "counting" homeless people across the globe relies heavily on who is considered a homeless person. Homeless individuals, and by extension refugees, can be seen as lacking lack the "crucible of our modern society" and lacking a way of actively belonging to and engaging with their respective communities or cultures[206] As Casavant demonstrates, a spectrum of definitions for homelessness, called the "continuum of homelessness", should refer to refugees as homeless individuals because they not only lose their home, but they are also afflicted with a myriad of problems that parallel those affecting the domestic homeless, such as "[a lack of] stable, safe and healthy housing, an extremely low income, adverse discrimination in access to services, with problems of mental health, alcohol, and drug abuse or social disorganization".[207] Refugees, like the domestic homeless, lose their source of identity and way of connecting with their culture for an indefinite period of time.

Thus, the current definition of homelessness unfortunately allows people to simplistically assume that homeless people, including refugees, are merely "without a place to live" when that is not the case. As numerous studies show, forced migration and displacement brings with it another host of problems including socioeconomic instability, "increased stress, isolation, and new responsibilities" in a completely new environment.[208]

For people in Russia, especially the youth, alcohol and substance use is a major cause and reason for becoming and continuing to be homeless.[209] The United Nations Centre for Human Settlements (UN-Habitat) wrote in its Global Report on Human Settlements in 1995: "Homelessness is a problem in developed as well as in developing countries. In London, for example, life expectancy among homeless people is more than 25 years lower than the national average."

Poor urban housing conditions are a global problem, but conditions are worst in developing countries. Habitat says that today 600 million people live in life- and health-threatening homes in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. For example, more than three in four young people had insufficient means of shelter and sanitation in some African countries like Malawi.[210] "The threat of mass homelessness is greatest in those regions because that is where population is growing fastest. By 2015, the 10 largest cities in the world will be in Asia, Latin America, and Africa. Nine of them will be in developing countries: Mumbai, India – 27.4 million; Lagos, Nigeria – 24.4; Shanghai, China – 23.4; Jakarta, Indonesia – 21.2; São Paulo, Brazil – 20.8; Karachi, Pakistan – 20.6; Beijing, China – 19.4; Dhaka, Bangladesh – 19; Mexico City, Mexico – 18.8. The only city in a developed country that will be in the top ten is Tokyo, Japan – 28.7 million."[211]

In 2008, Dr. Anna Tibaijuka, executive director of UN-HABITAT, referring to the recent report "State of the World's Cities Report 2008/2009",[212] said that the world economic crisis we are in should be viewed as a "housing finance crisis" in which the poorest of poor were left to fend for themselves.[213]

By country [edit]

Australia [edit]

A homeless person's shelter under a fallen willow tree in Australia

In Australia the Supported Accommodation Assistance Program (SAAP) is a joint Commonwealth and state government program which provides funding for more than 1,200 organizations which are aimed to assist homeless people or those in danger of becoming homeless, as well as women and children escaping domestic violence.[214] They provide accommodation such as refuges, shelters, and half-way houses, and offer a range of supported services. The Commonwealth has assigned over $800 million between 2000 and 2005 for the continuation of SAAP. The current program, governed by the Supported Assistance Act 1994, specifies that "the overall aim of SAAP is to provide transitional supported accommodation and related support services, in order to help people who are homeless to achieve the maximum possible degree of self-reliance and independence. This legislation has been established to help the homeless people of the nation and help rebuild the lives of those in need. The cooperation of the states also helps enhance the meaning of the legislation and demonstrates their desire to improve the nation as best they can." In 2011, the Specialist Homelessness Services (SHS) program replaced the SAAP program.[215]

Canada [edit]

Homelessness in Canada has grown in hugeness and complexity since 1997.[216] While historically known as a crisis only of urban centres such as Montreal, Laval, Vancouver, Edmonton, Calgary, and Toronto, increasing homelessness in suburban communities requires new services and resources.[217]

In recent years homelessness has become a major social issue in Canada. In Action Plan 2011, the Federal Government of Canada proposed $120 million annually from April 2014 until April 2019—with $70 million in new funding—to renew its Homelessness Partnering Strategy (HPS). In dealing with homelessness in Canada, the government focus is on the Housing First model. Thus, private or public organizations across Canada are eligible to receive HPS subsidies to implement Housing First programs. Canada spends more than 30 billion annually on social service programs for the homeless.[218]

China [edit]

In 2011, there were approximately 2.41 million homeless adults and 179,000 homeless children living in the country.[219] However, one publication estimated that there were one million homeless children in China in 2012.[220]

Housing in China is highly regulated by the Hukou system. This gives rise to a large number of migrant workers, numbering at 290.77 million in 2019.[221] These migrant workers have rural Hukou, but they move to the cities in order to find better jobs, though due to their rural Hukou they are entitled to fewer privileges than those with urban Hukou.[ citation needed ] According to Huili et al.,[222] these migrant workers "live in overcrowded and unsanitary conditions" and are always at risk of displacement to make way for new real estate developments. In 2017, the government responded to a deadly fire in a crowded building in Beijing by cracking down on dense illegal shared accommodations and evicting the residents, leaving many migrant laborers homeless.[223] This comes in the context of larger attempts by the government to limit the population increase in Beijing, often targeting migrant laborers.[224] However, according to official government statistics,[221] migrant workers in China have an average of 20.4 square metres (220 sq ft) of living space per capita, and the vast majority of migrant workers have basic living facilities such as heating, bathing, refrigerators, and washing machines.

Several natural disasters have led to homelessness in China. The 2000 Yunnan earthquake left 92,479 homeless and destroyed over 41,000 homes.[225]

Homelessness among people with mental health problems is 'much less common' in China than in high-income countries, due to stronger family ties, but is increasing due to migration within families and as a result of the one-child policy. A study in Xiangtan found at least 2439 schizophrenic people that have been homeless on a total population of 2.8 million. It was found that "homelessness was more common in individuals from rural communities (where social support services are limited), among those who wander away from their communities (i.e., those not from Xiangtan municipality), and among those with limited education (who are less able to mobilize social supports). Homelessness was also associated with greater age; [the cause] may be that older patients have 'burned their bridges' with relatives and, thus, end up on the streets."[226]

During the Cultural Revolution a large part of child welfare homes were closed down, leaving their inhabitants homeless. By the late 1990s, many new homes were set up to accommodate abandoned children. In 1999, the Ministry of Civil Affairs estimated the number of abandoned children in welfare homes to be 66,000.[227]

According to the Ministry of Civil Affairs, China had approximately 2,000 shelters and 20,000 social workers to aid approximately 3 million homeless people in 2014.[228]

From 2017 to 2019, the government of Guangdong Province assisted 5,388 homeless people in reuniting with relatives elsewhere in China. The Guangdong government assisted more than 150,000 people over a three-year period.[229]

In 2020, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Chinese Ministry of Civil Affairs announced several actions of the Central Committee in response to homelessness, including increasing support services and reuniting homeless people with their families.[230] In Wuhan, the situation for homeless people was particularly bad, as the lockdown made it impossible for homeless migrants to return to other parts of the country. The Wuhan Civil Affairs Bureau set up 69 shelters in the city to house 4,843 people.[231]

Denmark [edit]

Homelessness in Denmark is considered a significant social issue in the country.[232] [233] Since 2007, comprehensive counts have been performed every other year in week six (early February). The latest, from 2017, counted 6,635 homeless people in Denmark.[234] [235] The total number of people experiencing homelessness at some point in 2017 was estimated at 13,000,[234] while earlier estimates have placed it between 10,000 and 15,000.[236] Roughly half the homeless are in the Capital Region.[235] When compared to many other countries, such as the United States, the rate of Denmark's homeless is significantly lower, which has been linked to the relatively comprehensive welfare system.[237]

The number of homeless people in Denmark has risen in recent decades, but this has been most pronounced in people that are between 18 and 29 years old (although 30 to 59 years old remains the largest age group, at 70%), women (although men remains the largest group, at 75%) and immigrants (although Danish citizens remain the largest group).[234] [235] [238] [239] Among the foreign, a high percentage are Eastern or Southern European men that seek work in Denmark.[239] Many of these only stay in Denmark during the summer, returning to their respective countries during the relatively cold Danish winter.[240]

Based on the comprehensive count in February 2017, roughly one-tenth of homeless people in Denmark are "street sleepers" (which also includes people sleeping in stairways, sheds and other places not intended for human habitation), with the remaining sleeping in the homes of friends/family, in hotels/hostels, in shelters or alike.[234] [235] The number of street sleepers is higher during the summer,[234] and homeless foreigners are overrepresented among them.[240] Among homeless in Denmark, the primary issue is psychiatric disease at 36% (24% receive treatment), drug addiction at 27% (17% receive treatment) and alcohol addiction at 23% (9% receive treatment). Overall it is estimated that more than half of all homeless people have mental health issues.[235] Compared to many other countries such as the United States, a higher percentage of Denmark's homeless have mental health issues or substance abuse, as countries with weaker welfare systems tend to have higher homeless rates but the homeless will more likely to include from a wide range of groups.[237]

The government of Denmark's approach to homelessness include commissioning national surveys on homelessness during the last decade that allow for direct comparison between Denmark, Norway and Sweden.[241] The three countries have very similar definitions of homelessness, with minor variations.[242]

Egypt [edit]

Homelessness in Egypt is a significant social issue affecting some 12 million people in the country. Egypt has over 1,200 areas designated for irregular dwellings that do not conform to standard building laws, allowing homeless people to build shacks and other shelters for themselves.[243]

Reportedly, in Egypt, homelessness is defined to include those living in marginal housing.[244] Some scholars have stated that there is no agreed upon definition of homelessness in Egypt due to the difficulties government would face if an official definition were accepted.[245]

According to UNICEF, there are 1 million children living on the streets in Egypt.[246] Other researchers estimate the number to be some 3 million.[247] Homelessness NGOs assisting street children include those such as Hope Village Society,[246] and NAFAS.[244] Other NGOs, such as Plan International Egypt, work to reintegrate street children back into their families.[248]

Finland [edit]

Homelessness in Finland affects approximately 4 thousand people.[249]

In Finland the municipalities are required by law to offer apartments or shelters to every Finnish citizen who does not have a residence. In 2007 the center-right government of Matti Vanhanen began a special program of four wise men modeled after a US-originated Housing First policy to eliminate homelessness in Finland by 2015.[250] [251]

Finland is the only European Union country where homelessness is currently falling.[252] The country has adopted a Housing First policy, whereby social services assign homeless individuals rental homes first, and issues like mental health and substance abuse are treated second.[253] [254] Since its launch in 2008, the number of homeless people in Finland has decreased by roughly 30%, and the number of long-term homeless people has fallen by more than 35%.[252] "Sleeping rough", the practice of sleeping outside, has been largely eradicated in Helsinki, where only one 50-bed night shelter remains.[252]

The Constitution of Finland mandates that public authorities "promote the right of everyone to housing".[255] In addition, the constitution grants Finnish citizens "the right to receive indispensable subsistence and care", if needed.[255]

Since 2002, the Night of the Homeless event has been hosted throughout the country.[256] The events include demonstrations, food distribution, and movie screenings, among other activities.[257]

A "night café" in Helsinki, Kalkkers (run by the non-governmental organisation Vailla vakinaista asuntoa ry), operates as a temporary overnight resting place for approximately 15 people each night.[258] [259] Here showers, a meal and place to be with no questions asked is provided.

France [edit]

Homelessness in France is a significant social issue that is estimated to affect around 300,000 people - a figure that has doubled since 2012 (141,500) and tripled since 2001 (93,000). Around 185,000 people are currently staying in shelters, some 100,000 are in temporary housing for people seeking asylum and 16,000 live in slums.[260] [261] [262]

One study of homeless in Paris found that homeless people have a high degree of social proximity to other people living in conditions of poverty.[263] And terms in the media used to describe homelessness are formed around poverty and vagrancy.[264]

Some researchers maintain that a Housing First policy would not solve the homelessness issue in France.[265] [266]

Some researchers maintain that industrial restructuring in France led to the loss of some jobs among blue-collar workers whose skills did not transfer readily to other job sectors, which in turn led to a rise in homelessness.[267]

Homeless children in France is not a new phenomenon; the writer Emile Zola wrote about homeless children in late nineteenth century France.[268]

The homeless emergency number in France is 115.[269] The line is operated by SAMU Social.[ citation needed ]